The smallest railroads are often the most interesting.

And the Green Bay & Western Railroad packed a lot of fascination into just 248 miles of mainline and precious few branchlines.

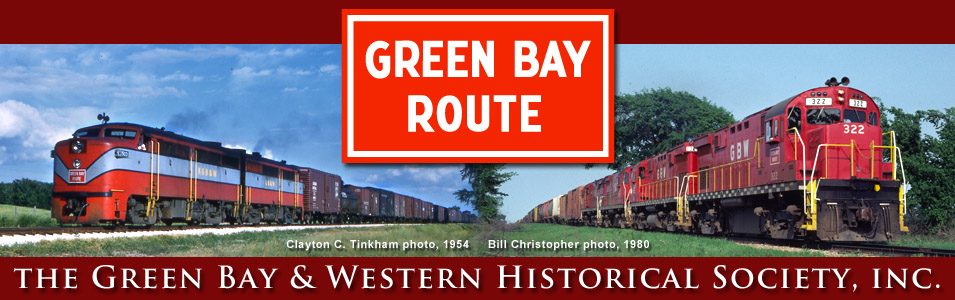

The GBW was famous for Alco power, the Harley-Davidsons of diesel locomotion. They were an Alco customer since the 19th Century, even before steam locomotive builders like Brooks, Dickson and Schenectady merged to form the American Locomotive Company. Every diesel the GBW ever owned – from the HH660 they bought in 1938, to the FA1s and RS2s that banished steam, to their 16-unit fleet when the railroad passed into history in 1993 – was a snorting, smoking, four-stroke product of Schenectady, New York.

But the GBW was much more than Alcos. For most of their history, their eastern connection was a fascinating cross-lake carferry operation. From 1892 to 1990, sturdy vessels of the Ann Arbor Railroad and the Pere Marquette Railway (later the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway) battled November storms and winter ice to force railroad reliability upon treacherous Lake Michigan. In the 1950s, hundreds of freight cars moved across the lake every day, and even though this market would eventually vanish, you can still ride a carferry across Lake Michigan.

The carferries were the GBW’s lifeblood for decades. Yet, when they disappeared, the GBW still had enough on-line business, especially paper, to keep it healthy – and make it an attractive target for a larger railroad system.

Even as the railroad roared on into the future, it remained tied to its past. The GBW had no power switches, and the only signals protected crossings with other railroads. In the 1990s, you could see Alcos hauling intermodal traffic every day, with a caboose bring up the rear. The GBW understood the importance of every customer and the value of every load at a time when the big railroads were adopting a “hook and haul” mentality. Perhaps no railroad went through fewer changes than the GBW while surviving and prospering for 127 years.

|

And the GBW was much more than trains and track. It was a friendly railroad to the interested and responsible observer. If you spent much time along the GBW, you likely became friends with some of the fine people who worked for it. Family connections were important; some employees counted three, four and even five generations of their family working for the GBW. It even had a father and son succession of presidents. |

The GBW was chartered in 1866 as the Green Bay & Lake Pepin Railway. At the time, many railroads tried to link major waterways, and in 1873 the railroad, then called the Green Bay & Mississippi, linked the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. Ultimately it ran from the Lake Michigan port of Kewaunee to Green Bay and west through the paper mill town of Wisconsin Rapids to the Mississippi River at Winona, Minnesota, the only place where it left the state of Wisconsin. The GBW even had a subsidiary on its east end, the Ahnapee & Western, which was twice independent and twice a part of the GBW.

Early on, however, the railroad was a financial failure. Traffic was sparse in the Wisconsin wilderness; passenger trains never found a real home on the “Grab Baggage & Walk.” The railroad’s resources were drained by derailments, roundhouse fires and floods. The GB&M would emerge from bankruptcy in 1881 as the Green Bay, Winona & St. Paul Railroad, only to go bankrupt again and emerge in 1896 as the Green Bay & Western Railroad.

Even by the standards of the time, the GBW was a lightweight railroad. Most of the locomotives were 4-4-0s, and they rode on spindly 56-pound rail. As the 20th Century progressed, however, new business would improve the railroad’s health. The carferries brought much-needed overhead traffic, as did a new Ford automobile plant in St. Paul. |

|

But the Great Depression dealt a heavy blow to the marginal railroad. Its frugal president, Frank B. Seymour, managed to keep the railroad alive. But it took a visionary man to see a prosperous future for the GBW. Homer E. McGee, a former Katy executive, became president of the GBW in 1934 and began an upgrading program that would improve the railroad’s track, rolling stock and financial health over the coming decades.

Increased traffic during World War II, along with the state’s growing industrial base, helped transform the “two streaks of rust across Wisconsin” into a respectable railroad. The carferries enjoyed their best years in the 1950s, feeding the GBW’s traffic base. With few modern steam locomotives, the GBW dieselized in 1950, often paying cash for their new Alcos instead of financing them.

In 1962 Homer McGee was succeeded as president by his son, Weldon McGee, who followed his father’s philosophy of conservative finances and continuous improvement. But the 1960s were a tough decade for the railroad industry as trucks ate into their traffic. Eventually the younger McGee decided the GBW would be better off as part of a larger system. |

|

The Burlington Northern attempted to buy the GBW in 1976, but thanks to resistance from the GBW’s neighbors – the Chicago & North Western, the Milwaukee Road, and the Soo Line – the deal was rejected by the Interstate Commerce Commission. Instead, the GBW was purchased by Itel, which owned other railroads and operated a large fleet of freight cars.

Thanks mostly to the paper business, the GBW continued to prosper, making it attractive to a larger system. On August 28, 1993, the GBW was purchased by the Wisconsin Central Limited. Its traffic and employees were absorbed by the WC, and the remaining Alcos were dispersed to other short lines across the U.S. Today, two-thirds of the GBW’s mainline remains in service as part of the Canadian National.

In spite of having been gone for almost 25 years, today there is more interest than ever in the fascinating little railroad that ran Alcos across Wisconsin. The Green Bay & Western Historical Society was created to collect and preserve the history of the GBW and make it accessible to the people who remember it, and to the people who wish they had the opportunity to experience it.

Click here for more information about the GBW’s history, route, locomotives, rolling stock, modeling information, and much more.

Green Bay & Western System Map

This system map, from the 1947-1956 period, is typical of the distorted maps railroads used to advertise their route. Of course the GBW wasn't absolutely straight, especially the east and west ends! But it does show practically every town the GBW ran through, as well as its railroad connections at the time, including those on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. Use the scroll bar at bottom to see the eastern end of the GBW, including Green Bay and Kewaunee, as well as the Ahnapee & Western.